External Sources of Exercises - Soltis' book Studying Chess Made Easy (starting on p.131) - de la Maza's book Rapid Chess Improvement - Suggest another source?

1. Beginning Exercises

1.1 Knight Obstacle Course

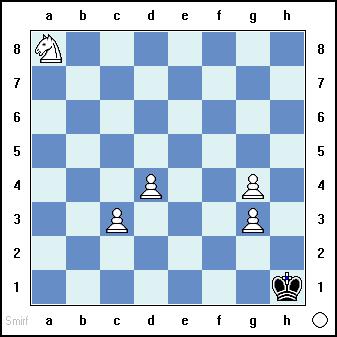

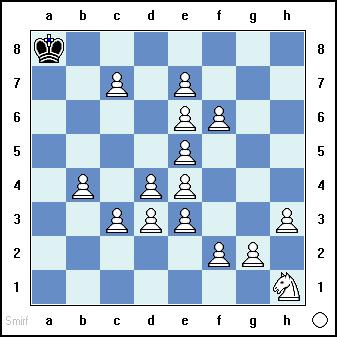

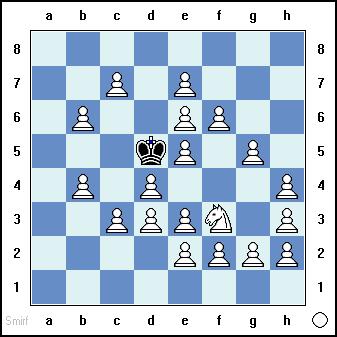

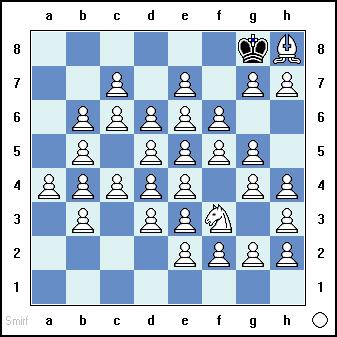

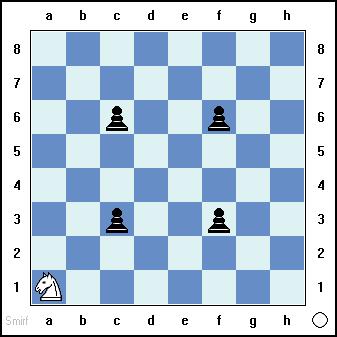

This is a variation many students love – especially those who love chess mazes. I place a Knight and a King of the Opposite Color on the board in any position except a Knight’s move apart. I then add many obstacles in the form of all the other pieces (it doesn’t matter their color – only the Knight and the Opposite Color King matter). The Knight has to make as many consecutive Knight moves as it takes to “capture” the King. The following are some (increasingly harder) example “Obstacle Courses” with the White Knight trying to capture the Black King and the White pawns as obstacles.

1.1 Knight Obstacle Course

This is a variation many students love – especially those who love chess mazes. I place a Knight and a King of the Opposite Color on the board in any position except a Knight’s move apart. I then add many obstacles in the form of all the other pieces (it doesn’t matter their color – only the Knight and the Opposite Color King matter). The Knight has to make as many consecutive Knight moves as it takes to “capture” the King. The following are some (increasingly harder) example “Obstacle Courses” with the White Knight trying to capture the Black King and the White pawns as obstacles.

A. The above maze for beginners requires care to get to f2 such as: Nb6-c4-b2-d1-f2-xh1 OR Nf7-d6-g5-e4-f2-xh1 etc.

B. The above easy maze has many solutions such as Ng3-f5-d6-c8-b6-xa8

C. This slightly harder maze has also many solutions such as Nd2-e4-g3-h5-f4-xd5

D. In the above diagram, White must go something like Nd2-f1-g3-h5-f4-g6-f8-d7-c5-b7-d8-f7-h6-xg8!

(To make this easier, remove the pawn on b4 or the one at h8!)

(To make this easier, remove the pawn on b4 or the one at h8!)

E. Here try Ng1-h3-f2-h1-g3-h5-f6-h7-f8-g6-h8-f7-d8-b7-c5-a6-b4-a2-c3-b1-a3-c4-xe3!

The above exercise can be done with other pieces, such as Rooks and Bishops, although the Knight is the most “fun.”

1.2 Minimal Piece Paths

In this exercise I invented the student is asked to find the shortest path to capture a King with multiple moves of a particular piece, and each time he does so successfully that path is rendered impossible by adding a blocking piece, like a pawn.

For example, suppose the moving piece is a Rook and the Rook is on c3 and the King on g6. At first these will be the only pieces on the board. Suppose the student first finds the two-move path Rc3-c6xg6. Then add a pawn to block that path, say on c5:

1.2 Minimal Piece Paths

In this exercise I invented the student is asked to find the shortest path to capture a King with multiple moves of a particular piece, and each time he does so successfully that path is rendered impossible by adding a blocking piece, like a pawn.

For example, suppose the moving piece is a Rook and the Rook is on c3 and the King on g6. At first these will be the only pieces on the board. Suppose the student first finds the two-move path Rc3-c6xg6. Then add a pawn to block that path, say on c5:

Now the student must try and find another two-move path, which in this case is Rc3-g3xg6. That path is then also blocked, let's say with a pawn at f3. This then eliminates all two-move paths so the student is instructed to find a three move path. Suppose he then finds Rc3-e3-e6xg6. Then this path is also blocked, say with a pawn on e6:

The student is then asked to find another three move capture with the Rook, say Rc3-c1-g1xg6, whereupon that path is also blocked at some point. This continues until all possible paths to capture the King in any number of moves is impossible. The exercise can then be repeated with either the Rook and King on different squares, or the Rook replaced by another pieces, say a Bishop or Knight.

1.3 Fritz Board Vision Exercises - Take that link: for those who own the chess engine "Fritz"

1.4 Recording Algebraic Notation Exercise - If you know how to take notation, i.e. record a chess game (note: there is no such chess verb "notating"!), and want to get to the point where you don't have to think about it, this is the exercise for you. The idea is to do it frequently within a short period of time. Find a chess board with no notation on the edges, or use masking tape to mask out the letters and numbers because you don't want these as a crutch. Since algebraic notation is from White's point of view, it makes sense to start with White. So play the White side of a chess game at least 7 times within a one-week span, recording all moves for both sides. Then repeat this with the Black pieces. This will give you the experience of playing about 280 moves from each side of the board within a short period of time. The level of competition does not matter; in fact, this is the one rare instance where you could even play yourself since the idea is to record the moves correctly and quickly, and not to get a good game.

1.3 Fritz Board Vision Exercises - Take that link: for those who own the chess engine "Fritz"

1.4 Recording Algebraic Notation Exercise - If you know how to take notation, i.e. record a chess game (note: there is no such chess verb "notating"!), and want to get to the point where you don't have to think about it, this is the exercise for you. The idea is to do it frequently within a short period of time. Find a chess board with no notation on the edges, or use masking tape to mask out the letters and numbers because you don't want these as a crutch. Since algebraic notation is from White's point of view, it makes sense to start with White. So play the White side of a chess game at least 7 times within a one-week span, recording all moves for both sides. Then repeat this with the Black pieces. This will give you the experience of playing about 280 moves from each side of the board within a short period of time. The level of competition does not matter; in fact, this is the one rare instance where you could even play yourself since the idea is to record the moves correctly and quickly, and not to get a good game.

2 Intermediate Exercises

2.1 Woolum Chessmazes

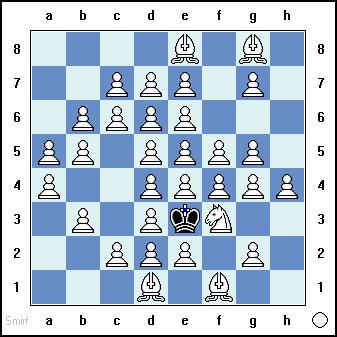

Chessmazes can be found in the back of Al Woolum's book Chess Tactics Handbook and now in Bruce Albertson's book Chess Mazes. In these mazes, like many of the above exercises, only one piece can move. The idea is to move that piece a certain number of times consecutively and capture the opposition's King without making going to any square where it captures an enemy piece or would be attacked by an enemy piece. Unlike the minimal path exercise, the path is only followed once and no pieces are added to the board. Usually there is only one way to do this and it is impossible to do it more quickly. For example, in the following position Woolum says White is to only move the Bishop and capture the Black King in 9 moves:

2.1 Woolum Chessmazes

Chessmazes can be found in the back of Al Woolum's book Chess Tactics Handbook and now in Bruce Albertson's book Chess Mazes. In these mazes, like many of the above exercises, only one piece can move. The idea is to move that piece a certain number of times consecutively and capture the opposition's King without making going to any square where it captures an enemy piece or would be attacked by an enemy piece. Unlike the minimal path exercise, the path is only followed once and no pieces are added to the board. Usually there is only one way to do this and it is impossible to do it more quickly. For example, in the following position Woolum says White is to only move the Bishop and capture the Black King in 9 moves:

The solution here is Be1-b4-a3-b2-g7-h6-e3-g1-h2xb8.

See also Bruce Alberston's Chess Maze books. In these mazes the rules are slightly different - you can make a capture so long as the moving piece is not subject to capture (i.e., never attacked). That rule change actually allows for much more difficult puzzles.

2.2 The “Chess IQ” test

I first saw this when it was published over 30 years ago in Chess Life:

See also Bruce Alberston's Chess Maze books. In these mazes the rules are slightly different - you can make a capture so long as the moving piece is not subject to capture (i.e., never attacked). That rule change actually allows for much more difficult puzzles.

2.2 The “Chess IQ” test

I first saw this when it was published over 30 years ago in Chess Life:

Perform a "knight tour" of legal White Knight moves to land, in order, from a1 to b1 to c1 to … h1 to h2 to f2 to c2 to a2 to a3 …zig-zagging right, up, then left and then back again until reaching all of the squares along the first rank (a8 is the final square). You must avoid moving to any squares where the black pawns reside AND the squares the black pawns attack. In other words, g2, e2, d2, b2, f3, c3, etc. can never be landed upon during the entire exercise – they are neither target squares nor can be used to get to target squares! The test is timed.

The original article on this test said that once a student has a modicum of board vision, this exercise can be used to test aptitude “independent” of chess knowledge. The student is supposed to take the test twice, one trial right after another. The tutor adds a penalty for each illegal move (I think the penalty was 10 seconds). The speed of the first test measures raw aptitude and the gain in time for the second try measures learning ability. Supposedly a first attempt taking five minutes or less shows International Master potential, while three minutes or less shows Grandmaster potential. (Believe it or not, the first time I took the test it took me about two minutes!! - and after some practice, I was able to do it in less than a minute! – But since I started playing serious chess at 16, I knew I never was going to become a Grandmaster, but that is another story – see my second book, The Improving Annotator: From Beginner to Master).

2.3 Knight Tours

You can get standard Knight tours from a site in Chessville.

2.4 Move the Pieces Against the Computer (all levels!) - suggested by Santiago Ferrera"

"I set my chess computer in 2200 elo strength ( i am about 1600), and i play with another board where I can analyze and move the pieces as much as I want, before I decide for the next move.

This has been great for me, because:

1) I can analyze with perfect order (i follow my algorithm consciously, I even have it printed near the

board to follow it step by step), and play Real Chess

2) For amateurs, its easier to catch your thinking errors if you see the final position of your analysis

in a real board

3) Your thinking gets automatically deeper, because as you analyzed 10 or 15 variants and 4 candidate moves,

you begin to understand the core of the position, which by only visualizing is very difficult at this level.

I hope you find this useful, and send you a big virtual tequila-shot from Mexico City."

2.5 Development Scoring (from Steve Eddins)

I thought about the issue of "improve your pieces" in terms of at-home study time, and I came up with an experimental exercise:

Annotate your game as follows:

Make an annotation following each of your opponent's moves, unless your next move is in book or is dictated by some tactical consideration. In the annotation following your opponent's move, list your least active pieces (typically one to three).

After your own subsequent move, give yourself one point for improving one of the pieces on that list; zero points otherwise.

My "score" on the game where I lost after being up a piece was in the neighborhood of 3 out of 18. For my victory last week it was more like 11 out of 17.

I've done this exercise on four of my games. It's very simple and quick to do, as long as you don't get too hung up on perfectly deciding which moves to score and which were legitimately constrained by tactics. Being simple and quick is important for an adult player like me whose study time is limited.

I think it might be a useful exercise for Class C players and below who have trouble using all their pieces.

Let me know how this works for you.

2.6 Deep Thinking (aka "20 minute exercise")

This is kind of a "half Stoyko" (see 3.1) exercise good for improving your analytical skills: Take a dynamic position and think for 20 minutes about what you would do, just as you would in a slow game where you have lots of time and Trigger 2 tells you that 20 minutes is reasonable. This is in lieu of having enough slow games where you can take 20 minutes on a move (i.e., if you can't play many games at 40/2 or thereabouts). Make sure to "move the pieces in your head" and try to visualize the possible lines. Analyze as clearly as possible. This exercise should be a decent substitute for slow chess (if you don't have time to play 40/2 games) and help increase your board vision. When you are done, check your analysis with a strong player or chess engine.

Ironically, only about a day after I wrote this, I read that GM Rowson recommended an almost identical exercise on pages 65-66 of his excellent training book Chess for Zebras.

2.7 ICC Checkmate with B and N

Although endgames with bishop and knight vs. King are rather rare, practicing this endgame has great side-effect benefits of developing board vision and piece coordination. So if you are a member of the ICC, just type "play KBNK" and practice this endgame!

2.8 Play out resignations

Take positions from game books where grandmasters resign against other grandmasters. Unless it seems to be a trivial mate, don't look at the analysis, but instead play out the final position, taking the winner's side and giving a strong computer engine the loser's side. See if you can win anyway. Helps develop good technique!

2.9 Play "Progressive Chess" - this helps force you to look ahead - if not to mate, then to prevent checkmate!

2.10 Tabiya Exercise: This exercise is similar to what Chess Openings Wizard does in its training mode, except it's done with a training partner or instructor. The training partner plays openings lines and you, as his/her opponent, rattle off the moves you would play against that line immediately. As soon as you arrive at a move where you're not 100% sure what to do, you stop and look up that move in an opening book or database. The training partner would then try another line (the friend can do this with either color), etc.

2.11 Find the Candidates: Pick a random position & try to find all the moves which evaluate as within 0.3 of the best move. Then let an engine find the best N moves & see how many of the top candidates you found, or moves you thought were strong candidates but were not within 0.3 of the best.

3 Advanced Exercises

3.1 Stoyko Exercise

This exercise was suggested to me by FM Steve Stoyko, and I suggest it for intermediate/strong players who wish to improve their visualization and evaluation capabilities.

First the reader should find a rich middlegame position. Suggestions would be go go to most any Kasparov, Shirov, or Speelman game, or perhaps from the books:

When you are done, either take the analysis to a good instructor, player, or software program. Look at each line to see how well you visualized the position (any retained image problems, etc.?), and also compare your logic (was that move really forced?) and all your evaluations, as well as your PV.

Steve claimed that each time he did this exercise he gained about 100 rating points! :)

A summary of this exercise:

1) Find a fairly complicated/unbalanced position

2) Get out a pen/pencil and paper

3) You have unlimited time

4) Write down every (pertinent) line for as deep as you can see, making sure to include an evaluation at the end of the line. This will likely include dozens of lines and several first ply candidate moves. Evaluations can be any type you like:

a) Computer (in pawns, like +.3)

b) MCO/Informant (=, +/=, etc.)

c) English ("White is a little better")

5) At the end state which move you would play and it's "best play for both sides" line becomes the PV

6) When you are done, go over each line and its evaluation with a strong player and/or a computer. Look for:

a) Lines/moves you should have analyzed but missed

b) Any errors in visualization (retained images, etc.)

c) Any lines where you stopped analyzing too soon, thus causing a big error in evaluation (quiescence errors)

d) Any large errors in evaluation of any line

e) Whether the above caused you to chose the wrong move, etc.

Question about this exercise: "I don't understand your point: "The key is the amateur's evaluation of every line... you will have your instructor (or Fritz or whatever) compare your evaluation of every line, resulting in a really good evaluation test". How is it a "really good evaluation test" to analyze a single position from a Kasparov or Shirov type game for a hour or so? I can see how it's a good calculation/visualisation exercise - totally agreed. I've done it in the past for this benefit and I'd do it again. But I'm just not understanding the evaluation benefit?!"

Answer: Your question is very good (I guess if you misunderstand that purpose of the exercise, that would help explain my observation as to why so many players are missing out on a valuable resource!).

Most players are very poor at even-material evaluation. Therefore they make bad moves because, assuming they evaluate potential outcomes of various candidate moves, they choose a move that is not best because they erroneously think the resultant position(s) from their chosen move are better.

The second (non-analysis) aspect of the Stoyko exercise is to evaluate EVERY line that you examine in the tree - that could be dozens or even possibly hundreds of lines for one position since the Stoyko position has unlimited time. By comparing your evaluations of these hundreds of lines with your instructors' evaluation, you learn to improve one of the most critical skills you have - what is good and what is bad and why and how much. It also helps you identify the all-too-common quiescence errors where weak players stop their line too soon and therefore mis-evaluate because they did not look to see what might happen with further checks, captures, and threats.

This capability is so important and its failure so critical that you would think everyone would want to work on it, especially since the amount of work is an hour or two, plus additional time for going over it with someone (or even at worst via computer evaluation).

Here are two common mistakes when doing your first Stoyko exercise:

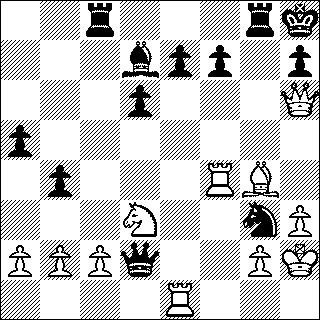

Example 1: from Bogoljubow-Alekhine, WC Match 1934 (analysis). Black to play:

The original article on this test said that once a student has a modicum of board vision, this exercise can be used to test aptitude “independent” of chess knowledge. The student is supposed to take the test twice, one trial right after another. The tutor adds a penalty for each illegal move (I think the penalty was 10 seconds). The speed of the first test measures raw aptitude and the gain in time for the second try measures learning ability. Supposedly a first attempt taking five minutes or less shows International Master potential, while three minutes or less shows Grandmaster potential. (Believe it or not, the first time I took the test it took me about two minutes!! - and after some practice, I was able to do it in less than a minute! – But since I started playing serious chess at 16, I knew I never was going to become a Grandmaster, but that is another story – see my second book, The Improving Annotator: From Beginner to Master).

2.3 Knight Tours

You can get standard Knight tours from a site in Chessville.

2.4 Move the Pieces Against the Computer (all levels!) - suggested by Santiago Ferrera"

"I set my chess computer in 2200 elo strength ( i am about 1600), and i play with another board where I can analyze and move the pieces as much as I want, before I decide for the next move.

This has been great for me, because:

1) I can analyze with perfect order (i follow my algorithm consciously, I even have it printed near the

board to follow it step by step), and play Real Chess

2) For amateurs, its easier to catch your thinking errors if you see the final position of your analysis

in a real board

3) Your thinking gets automatically deeper, because as you analyzed 10 or 15 variants and 4 candidate moves,

you begin to understand the core of the position, which by only visualizing is very difficult at this level.

I hope you find this useful, and send you a big virtual tequila-shot from Mexico City."

2.5 Development Scoring (from Steve Eddins)

I thought about the issue of "improve your pieces" in terms of at-home study time, and I came up with an experimental exercise:

Annotate your game as follows:

Make an annotation following each of your opponent's moves, unless your next move is in book or is dictated by some tactical consideration. In the annotation following your opponent's move, list your least active pieces (typically one to three).

After your own subsequent move, give yourself one point for improving one of the pieces on that list; zero points otherwise.

My "score" on the game where I lost after being up a piece was in the neighborhood of 3 out of 18. For my victory last week it was more like 11 out of 17.

I've done this exercise on four of my games. It's very simple and quick to do, as long as you don't get too hung up on perfectly deciding which moves to score and which were legitimately constrained by tactics. Being simple and quick is important for an adult player like me whose study time is limited.

I think it might be a useful exercise for Class C players and below who have trouble using all their pieces.

Let me know how this works for you.

2.6 Deep Thinking (aka "20 minute exercise")

This is kind of a "half Stoyko" (see 3.1) exercise good for improving your analytical skills: Take a dynamic position and think for 20 minutes about what you would do, just as you would in a slow game where you have lots of time and Trigger 2 tells you that 20 minutes is reasonable. This is in lieu of having enough slow games where you can take 20 minutes on a move (i.e., if you can't play many games at 40/2 or thereabouts). Make sure to "move the pieces in your head" and try to visualize the possible lines. Analyze as clearly as possible. This exercise should be a decent substitute for slow chess (if you don't have time to play 40/2 games) and help increase your board vision. When you are done, check your analysis with a strong player or chess engine.

Ironically, only about a day after I wrote this, I read that GM Rowson recommended an almost identical exercise on pages 65-66 of his excellent training book Chess for Zebras.

2.7 ICC Checkmate with B and N

Although endgames with bishop and knight vs. King are rather rare, practicing this endgame has great side-effect benefits of developing board vision and piece coordination. So if you are a member of the ICC, just type "play KBNK" and practice this endgame!

2.8 Play out resignations

Take positions from game books where grandmasters resign against other grandmasters. Unless it seems to be a trivial mate, don't look at the analysis, but instead play out the final position, taking the winner's side and giving a strong computer engine the loser's side. See if you can win anyway. Helps develop good technique!

2.9 Play "Progressive Chess" - this helps force you to look ahead - if not to mate, then to prevent checkmate!

2.10 Tabiya Exercise: This exercise is similar to what Chess Openings Wizard does in its training mode, except it's done with a training partner or instructor. The training partner plays openings lines and you, as his/her opponent, rattle off the moves you would play against that line immediately. As soon as you arrive at a move where you're not 100% sure what to do, you stop and look up that move in an opening book or database. The training partner would then try another line (the friend can do this with either color), etc.

2.11 Find the Candidates: Pick a random position & try to find all the moves which evaluate as within 0.3 of the best move. Then let an engine find the best N moves & see how many of the top candidates you found, or moves you thought were strong candidates but were not within 0.3 of the best.

3 Advanced Exercises

3.1 Stoyko Exercise

This exercise was suggested to me by FM Steve Stoyko, and I suggest it for intermediate/strong players who wish to improve their visualization and evaluation capabilities.

First the reader should find a rich middlegame position. Suggestions would be go go to most any Kasparov, Shirov, or Speelman game, or perhaps from the books:

- Dvoretsky's Analytical Manual,

- Aagaard's Calculation,

- How to Think in Chess or

- Genius in Chess.

- Another book that has both Stoyko and "de Groot" type positions is Gaprindashvili's "Critical Moments in Chess". Take out a paper and pencil.

When you are done, either take the analysis to a good instructor, player, or software program. Look at each line to see how well you visualized the position (any retained image problems, etc.?), and also compare your logic (was that move really forced?) and all your evaluations, as well as your PV.

Steve claimed that each time he did this exercise he gained about 100 rating points! :)

A summary of this exercise:

1) Find a fairly complicated/unbalanced position

2) Get out a pen/pencil and paper

3) You have unlimited time

4) Write down every (pertinent) line for as deep as you can see, making sure to include an evaluation at the end of the line. This will likely include dozens of lines and several first ply candidate moves. Evaluations can be any type you like:

a) Computer (in pawns, like +.3)

b) MCO/Informant (=, +/=, etc.)

c) English ("White is a little better")

5) At the end state which move you would play and it's "best play for both sides" line becomes the PV

6) When you are done, go over each line and its evaluation with a strong player and/or a computer. Look for:

a) Lines/moves you should have analyzed but missed

b) Any errors in visualization (retained images, etc.)

c) Any lines where you stopped analyzing too soon, thus causing a big error in evaluation (quiescence errors)

d) Any large errors in evaluation of any line

e) Whether the above caused you to chose the wrong move, etc.

Question about this exercise: "I don't understand your point: "The key is the amateur's evaluation of every line... you will have your instructor (or Fritz or whatever) compare your evaluation of every line, resulting in a really good evaluation test". How is it a "really good evaluation test" to analyze a single position from a Kasparov or Shirov type game for a hour or so? I can see how it's a good calculation/visualisation exercise - totally agreed. I've done it in the past for this benefit and I'd do it again. But I'm just not understanding the evaluation benefit?!"

Answer: Your question is very good (I guess if you misunderstand that purpose of the exercise, that would help explain my observation as to why so many players are missing out on a valuable resource!).

Most players are very poor at even-material evaluation. Therefore they make bad moves because, assuming they evaluate potential outcomes of various candidate moves, they choose a move that is not best because they erroneously think the resultant position(s) from their chosen move are better.

The second (non-analysis) aspect of the Stoyko exercise is to evaluate EVERY line that you examine in the tree - that could be dozens or even possibly hundreds of lines for one position since the Stoyko position has unlimited time. By comparing your evaluations of these hundreds of lines with your instructors' evaluation, you learn to improve one of the most critical skills you have - what is good and what is bad and why and how much. It also helps you identify the all-too-common quiescence errors where weak players stop their line too soon and therefore mis-evaluate because they did not look to see what might happen with further checks, captures, and threats.

This capability is so important and its failure so critical that you would think everyone would want to work on it, especially since the amount of work is an hour or two, plus additional time for going over it with someone (or even at worst via computer evaluation).

Here are two common mistakes when doing your first Stoyko exercise:

- A player takes a position that was far too balanced and almost still in book (too early in the game). Instead, you want to find “messy” positions which are unclear, usually because one side has sacrificed material for some other advantage. Also, when the line is balanced, then most of the evaluations are fairly balanced, and that is not good practice for evaluation. You can find these in the middle of lots of Shirov games, Kasparov games, Topalov games, or in books like Levitt’s Genius in Chess, Chapter 9 of Eingorn's Decision Making at the Chessboard, or Przewoznik and Soszynski’s How to Think in Chess, likely even in some of your own games.

- A player does not nearly enough analysis (which goes along with number 1, since a much more “regular” position has far fewer lines worth investigating). Usually a Stoyko position is unclear and you would have dozens of lines and hundreds of nodes in your analysis. On a sheet of paper, handwritten, this would take up around 3-4 sides of paper. Remember, since there is no time limit, you are trying to see as far as is pertinent in every possible line, so it can get fairly deep (which is why this exercise is good for testing your visualization).

Example 1: from Bogoljubow-Alekhine, WC Match 1934 (analysis). Black to play:

Example 2: From Shirov-Timman Belgrade 1995 (analysis). Black to play

Example 3: From Zhang-Moolten Gr. Philadelphia Championship 2005 (White to play):

Example 4: From a consultation game I played (White to play):

White: Kg1, Qe2, Rd1, Na4, Nf3, Bb6, Pawns a2,b2,e4,f2,g2,h2

Black: Ke8, Qd8, Rc1, Rh8, Bc8, Be7, Na5, Ng8, Pawns a6,d6,e6,f7,g7,h7

See also Chapter 9 of Eingorn's "Decision-Making at the Chessboard" book for many more Stoyko positions!

3.2 PV Exercise

Play a slow (G/60 or slower, but preferably G/90 or slower) practice game with a friend. It could be OTB or on-line, but you must record manually. In addition to recording the move and the time left (recommended standard practice), also write down your Principal Variation (PV) - the most expected line of play, along with your evaluation each time you move. Put your opponent's move down as normal. The test will be more instructive if both players do the exercise, but that is certainly not necessary - if just you do it, it should be fine.

So, for example, suppose you are White, and out of book in a G/75 game on move 17:

White Black

17. Nc4 (64 min) Be7 Nxb6 axb6 = Bd6

18. Nxb6 (62) axb6 Rac1 += axb6

19. Rfc1 (59) Rac8 Bxe5 fxe5 Qh4 += h6

20. Bxe5 (57) fxe5 Qh4 +/- fxe5

21. Qh4 (55) g6 Qxh6 Bf8 Qh4+- Rac8

etc.

In order left to right, this is the move number, actual white move, time remaining, PV (usually showing an extra 2-8 ply but not necessary on book moves, recaptures, etc.), evaluation after the PV (optional but helpful), and Black's move.

Note: Doing this exercise should take no extra time as you are writing this extra information while your opponent is thinking. But be careful to write down your PV as soon as you move - don't use your opponent's time to think more and then write what you find during his thinking time - the PV is supposed to reflect what you were thinking was going to happen at the time you made your move! You can of course think on your opponent's move and if that changes your PV, fine, but you should not change what you wrote right after your move.

Then after the game you can compare your PV's with your opponent's expectations at the same points and also see how your evaluations and PV's compare with his, Fritz or ChessMaster's. (This PV information is also a great subject for a lesson with me, or your instructor!) I would think this would be a super-excellent way to ensure that you play real chess on every move and consider all of your opponent's checks, captures, and threats, a prerequisite for becoming a good player. Also your evaluation skills should soar as you compare your evaluations with Fritz'.

3.3 Time Management Exercises

3.3.1 Diminishing Returns (30-2-7) Exercise

You want to take more time on critical moves and less time on non-critical moves. To prove to yourself that this is true, I have devised an exercise which tests how much better (or not!) you play when you take more time. Select a game of 40 or more moves and choose a color to play. After the "book" opening moves you know, pretend you are playing the game, except that you have a timer running which goes off after 30 seconds, 2 minutes, and 7 minutes for each move. When the timer goes off, write down the move you would play if you had to move at that time. That way for each position you will have three different moves chosen: the one at 30 seconds, 2 minutes, and 7 minutes. Then write the move actually played and then play the opponent's move.

When you are finished going thru the game, get a chess engine and put the four moves (30 seconds, 2 minute, 7 minute, and the actual move) into the engine and let it think for at least 12 ply, and then write down the four evaluations next to the moves. At the end of the game compare how you did on each move with the engine's evaluation. You should find that on critical, analytical moves the extra time was very helpful but on non-analytical, judgmental moves the extra times got diminishing returns.

On non-critical positions you should use good general principles and judgement and play relatively quickly. On critical moves you should mostly ignore general principles, use precise analysis, and take your time.

Another similar exercise for players that play the opening too slowly is the...

3.3.2 7th move exercise

Take some random GM games and take 30 seconds to decide the 7th move for Black (assuming you don't know the book move; if you do, go to the next game). Then compare your 7th move with the GM's move and a strong engine's analysis of its 7th move vs. yours (let the engine think for 12 ply or more). If your move is close (<~0.1 pawn) from either the GM's move or the engine's, then you are probably following good opening principles and should learn to trust your opening instincts and play a little faster, assuming you don't feel any danger.

3.3.3 Trigger 2 Eggtimer Exercise

One major problem for average players is determining what is "too fast" or "too slow" for a given move. That ideal time is based on the position, the move number, the time control, and how many minutes are left on your clock. I have dubbed the expiration of that ideal time “Trigger 2”, The whole idea comes down to criticality analysis, which is the major part of a skill I call micro time management. I have written several Novice Nooks on this, including The Two Move Triggers, Criticality Quiz, The Case for Time Management, etc.

The psychological aspects of playing too fast I wrote about in Slowing Down

To constantly move before Trigger 2, or to do so by a large margin, would play playing too fast.

There are two common types of errors you can make with Trigger 2:

1) You can badly estimate how much time is reasonable for the circumstances, or

2) You know approximately how much time would be reasonable for the move, but “let time fly when you are having fun” and not realize how much time has gone by.

If you think you have the second problem – you are able to determine Trigger 2 but have difficulty sensing when you have used that amount of time - using a separate clock or egg-timer set to “alarm” at that time is an exercise you can use during practice games and individual positions. Use the egg-timer like you would a simultaneous exhibition - when the timer goes off you have to move the best move you have found up to that time. Of course, if you find during the analysis that the move is much more critical than you thought, then Trigger 2 expands (gets longer). However, if you consistently take longer than a reasonable Trigger 2, you will find yourself in unnecessary time trouble, which is what this exercise is trying to minimize.

3.3.4 Trigger 2 Target Practice

The idea is to see if a player understands about how long he should take on a move, given the position and the time situation (and if he understands, why he takes a different amount of time). So:

1) Play a very slow game against a computer or a friend

2) After the opponent makes a move, take a few seconds (no more than 20 seconds, to be sure, but better only 5-10) to guesstimate about how much time would be reasonable to take for this move – write this time (“Trigger 2”) on your scoresheet. Then think and make your move normally.

Exceptions to #2 : A) Book moves

B) Forced moves or recaptures, which should be played immediately

In either of these exceptions, just make your move.

Special note: If your guesstimate changes during the move because you realize that the move is much more critical than you thought, then if you wish, as soon as you realize this you can cross off your estimate and put in the new, higher estimate.

3) At the end of the game go back and write down how much time you actually did take on each move (in a 2nd column)

Then we can compare your Trigger 2’s with your actual times to see why you are so slow.

3.4 The position trails the game by 6 ply (3 moves) - a visualization exercise

Play a game with a friend over-the-board, announce the moves, but only show the position as it was three moves (6 ply ago). For example, in the Ruy Lopez, after 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 only after 4.Ba4 would you see 1.e4. Then after say 4...Nf6 you would show 1...e5. This works on your visualization. If you are weaker, try less than 6 ply. If you are stronger, try more!

White: Kg1, Qe2, Rd1, Na4, Nf3, Bb6, Pawns a2,b2,e4,f2,g2,h2

Black: Ke8, Qd8, Rc1, Rh8, Bc8, Be7, Na5, Ng8, Pawns a6,d6,e6,f7,g7,h7

See also Chapter 9 of Eingorn's "Decision-Making at the Chessboard" book for many more Stoyko positions!

3.2 PV Exercise

Play a slow (G/60 or slower, but preferably G/90 or slower) practice game with a friend. It could be OTB or on-line, but you must record manually. In addition to recording the move and the time left (recommended standard practice), also write down your Principal Variation (PV) - the most expected line of play, along with your evaluation each time you move. Put your opponent's move down as normal. The test will be more instructive if both players do the exercise, but that is certainly not necessary - if just you do it, it should be fine.

So, for example, suppose you are White, and out of book in a G/75 game on move 17:

White Black

17. Nc4 (64 min) Be7 Nxb6 axb6 = Bd6

18. Nxb6 (62) axb6 Rac1 += axb6

19. Rfc1 (59) Rac8 Bxe5 fxe5 Qh4 += h6

20. Bxe5 (57) fxe5 Qh4 +/- fxe5

21. Qh4 (55) g6 Qxh6 Bf8 Qh4+- Rac8

etc.

In order left to right, this is the move number, actual white move, time remaining, PV (usually showing an extra 2-8 ply but not necessary on book moves, recaptures, etc.), evaluation after the PV (optional but helpful), and Black's move.

Note: Doing this exercise should take no extra time as you are writing this extra information while your opponent is thinking. But be careful to write down your PV as soon as you move - don't use your opponent's time to think more and then write what you find during his thinking time - the PV is supposed to reflect what you were thinking was going to happen at the time you made your move! You can of course think on your opponent's move and if that changes your PV, fine, but you should not change what you wrote right after your move.

Then after the game you can compare your PV's with your opponent's expectations at the same points and also see how your evaluations and PV's compare with his, Fritz or ChessMaster's. (This PV information is also a great subject for a lesson with me, or your instructor!) I would think this would be a super-excellent way to ensure that you play real chess on every move and consider all of your opponent's checks, captures, and threats, a prerequisite for becoming a good player. Also your evaluation skills should soar as you compare your evaluations with Fritz'.

3.3 Time Management Exercises

3.3.1 Diminishing Returns (30-2-7) Exercise

You want to take more time on critical moves and less time on non-critical moves. To prove to yourself that this is true, I have devised an exercise which tests how much better (or not!) you play when you take more time. Select a game of 40 or more moves and choose a color to play. After the "book" opening moves you know, pretend you are playing the game, except that you have a timer running which goes off after 30 seconds, 2 minutes, and 7 minutes for each move. When the timer goes off, write down the move you would play if you had to move at that time. That way for each position you will have three different moves chosen: the one at 30 seconds, 2 minutes, and 7 minutes. Then write the move actually played and then play the opponent's move.

When you are finished going thru the game, get a chess engine and put the four moves (30 seconds, 2 minute, 7 minute, and the actual move) into the engine and let it think for at least 12 ply, and then write down the four evaluations next to the moves. At the end of the game compare how you did on each move with the engine's evaluation. You should find that on critical, analytical moves the extra time was very helpful but on non-analytical, judgmental moves the extra times got diminishing returns.

On non-critical positions you should use good general principles and judgement and play relatively quickly. On critical moves you should mostly ignore general principles, use precise analysis, and take your time.

Another similar exercise for players that play the opening too slowly is the...

3.3.2 7th move exercise

Take some random GM games and take 30 seconds to decide the 7th move for Black (assuming you don't know the book move; if you do, go to the next game). Then compare your 7th move with the GM's move and a strong engine's analysis of its 7th move vs. yours (let the engine think for 12 ply or more). If your move is close (<~0.1 pawn) from either the GM's move or the engine's, then you are probably following good opening principles and should learn to trust your opening instincts and play a little faster, assuming you don't feel any danger.

3.3.3 Trigger 2 Eggtimer Exercise

One major problem for average players is determining what is "too fast" or "too slow" for a given move. That ideal time is based on the position, the move number, the time control, and how many minutes are left on your clock. I have dubbed the expiration of that ideal time “Trigger 2”, The whole idea comes down to criticality analysis, which is the major part of a skill I call micro time management. I have written several Novice Nooks on this, including The Two Move Triggers, Criticality Quiz, The Case for Time Management, etc.

The psychological aspects of playing too fast I wrote about in Slowing Down

To constantly move before Trigger 2, or to do so by a large margin, would play playing too fast.

There are two common types of errors you can make with Trigger 2:

1) You can badly estimate how much time is reasonable for the circumstances, or

2) You know approximately how much time would be reasonable for the move, but “let time fly when you are having fun” and not realize how much time has gone by.

If you think you have the second problem – you are able to determine Trigger 2 but have difficulty sensing when you have used that amount of time - using a separate clock or egg-timer set to “alarm” at that time is an exercise you can use during practice games and individual positions. Use the egg-timer like you would a simultaneous exhibition - when the timer goes off you have to move the best move you have found up to that time. Of course, if you find during the analysis that the move is much more critical than you thought, then Trigger 2 expands (gets longer). However, if you consistently take longer than a reasonable Trigger 2, you will find yourself in unnecessary time trouble, which is what this exercise is trying to minimize.

3.3.4 Trigger 2 Target Practice

The idea is to see if a player understands about how long he should take on a move, given the position and the time situation (and if he understands, why he takes a different amount of time). So:

1) Play a very slow game against a computer or a friend

2) After the opponent makes a move, take a few seconds (no more than 20 seconds, to be sure, but better only 5-10) to guesstimate about how much time would be reasonable to take for this move – write this time (“Trigger 2”) on your scoresheet. Then think and make your move normally.

Exceptions to #2 : A) Book moves

B) Forced moves or recaptures, which should be played immediately

In either of these exceptions, just make your move.

Special note: If your guesstimate changes during the move because you realize that the move is much more critical than you thought, then if you wish, as soon as you realize this you can cross off your estimate and put in the new, higher estimate.

3) At the end of the game go back and write down how much time you actually did take on each move (in a 2nd column)

Then we can compare your Trigger 2’s with your actual times to see why you are so slow.

3.4 The position trails the game by 6 ply (3 moves) - a visualization exercise

Play a game with a friend over-the-board, announce the moves, but only show the position as it was three moves (6 ply ago). For example, in the Ruy Lopez, after 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 only after 4.Ba4 would you see 1.e4. Then after say 4...Nf6 you would show 1...e5. This works on your visualization. If you are weaker, try less than 6 ply. If you are stronger, try more!